Sign up for CNN’s science newsletter Wonder Theory. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, never experienced a devastating population decline, according to an analysis of ancient DNA from 15 former inhabitants of the remote Pacific island.

The analysis also suggested that the inhabitants of the island, which lies about 3,700 kilometers from the South American mainland, reached America in the 14th century – long before Christopher Columbus landed in the New World in 1492.

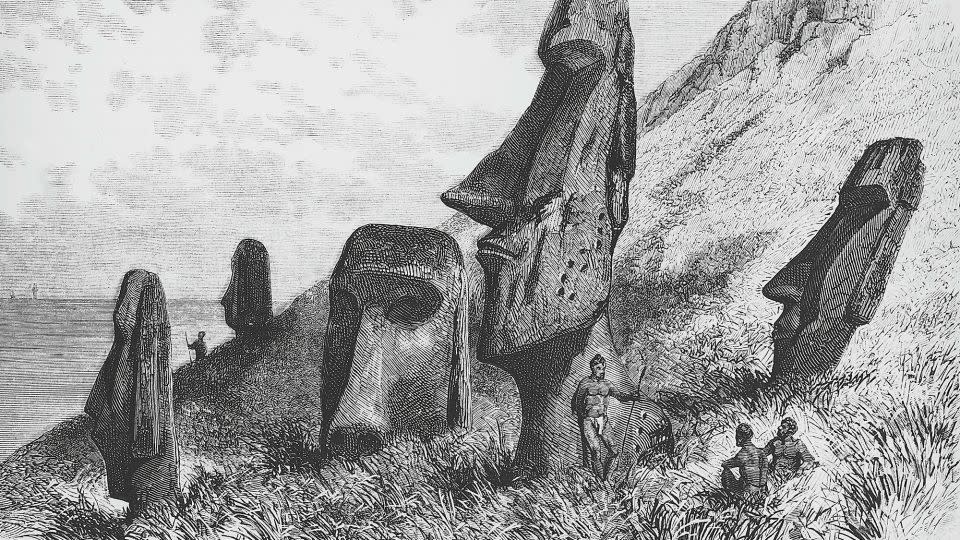

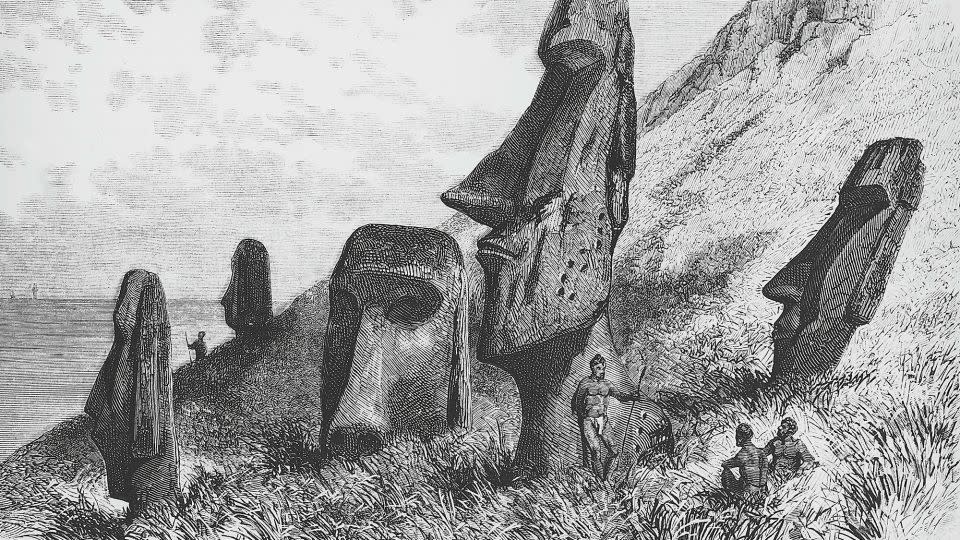

Settled by Polynesian sailors 800 years ago, Rapa Nui, now part of Chile, has hundreds of monumental stone heads that recall the past. The island has long been a place of fascination.

Some experts, such as geographer Jared Diamond, used Easter Island in his 2005 book Collapse as a cautionary tale of how the exploitation of limited resources can lead to catastrophic population declines, ecological devastation and the destruction of a society through internal power struggles.

But this theory remains controversial, and other archaeological finds suggest that Rapa Nui was home to a small but sustainable society.

With the new analysis, scientists have used ancient DNA for the first time to answer the question of whether Easter Island experienced a self-inflicted societal collapse, helping to shed light on the island’s mysterious past.

Genome of Easter Island

To further explore Rapa Nui’s history, researchers sequenced the genomes of 15 former inhabitants who lived on the island over the past 400 years. The remains are kept at the Musée de l’Homme, the Museum of Humanity, in Paris, part of the French National Museum of Natural History.

The researchers found no evidence of a genetic bottleneck associated with a sharp population decline, according to the study, published Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature.

Instead, the island was home to a small population whose size steadily increased until the 1860s, the analysis found. At that point, the study found, slave hunters from Peru forcibly expelled a third of the island’s population.

“It is definitely not a major population collapse, as is claimed, but a population collapse in which 80 or 90 percent of the population died,” said study co-author J. Víctor Moreno-Mayar, assistant professor of geogenetics at the Globe Institute at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

The genomes also revealed that Easter Island’s inhabitants had exchanged genes with an Amerindian population, suggesting that the inhabitants crossed the ocean to South America sometime between 1250 and 1430, before Columbus’ arrival in the Americas – and long before Europeans reached Rapa Nui in 1722.

About 6 to 11 percent of the individuals’ genomes can be traced back to ancestors who lived on the coast of South America, the study found. The team’s analysis provided information about when these two groups met and had offspring. The authors estimated that this happened 15 to 17 generations before the individuals studied.

Polynesian sailors

The discovery is not entirely surprising. Oral traditions and DNA analysis of modern-day islanders have suggested such an ancestry, and remains of the sweet potato imported from South America have been found on the island, dating back to before European contact, Moreno-Mayar said.

Some experts and the general public are reluctant to let go of the stories about the Easter Island disasters, says Lisa Matisoo-Smith, a professor of biological anthropology at the University of Otago in New Zealand.

But the ancient genomes add to growing evidence that the idea of a self-inflicted population collapse on Easter Island is false, says Matisoo-Smith, who was not involved in the study.

“We know that the original Polynesian sailors who discovered and settled Rapa Nui at least 800 years ago were among the world’s greatest sailors and travelers,” she said in a statement from New Zealand’s Science Media Centre.

“Their ancestors had lived in an oceanic environment for at least 3,000 years. They sailed eastward across thousands of miles of open ocean and found almost all of the habitable islands in the vast Pacific. It would be more surprising if they had not reached the coast of South America. These results provide some interesting clues about the timing of this contact.”

Matisoo-Smith noted that Pacific scholars have challenged the narrative of ecocide and societal collapse based on a range of archaeological evidence.

“But now we finally have evidence from ancient DNA that directly answers both of these questions and may allow us to focus on a more realistic portrayal of the history of this fascinating but actually rather typical Polynesian island,” she said.

A study published in June based on satellite images of land once used to grow food found a similar conclusion.

DNA analysis of human remains

The human remains used for the new DNA analysis were collected in 1877 by French scholar Alphonse Pinart and in 1935 by Swiss anthropologist Alfred Métraux, according to the latest study, which cites museum archives.

The circumstances under which the remains were stolen are unclear, the study says, but they are part of a broader trend of collecting remains from colonized areas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The research team worked with Rapa Nui communities and government institutions to gain consent for the study. The scientists said they hoped the results would help repatriate the remains so the individuals could be buried on the island.

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com